Welcome

Create your free Unicorn account to bid in our legendary weekly auctions.

By continuing, you agree to the Unicorn Terms of Use, Privacy Policy, Conditions of Sale, and to receive marketing and transactional SMS messages.

Already have an account?

Let’s get you approved to bid

To place your first bid, you’ll need to get approved to bid by confirming your mailing address and adding a payment method

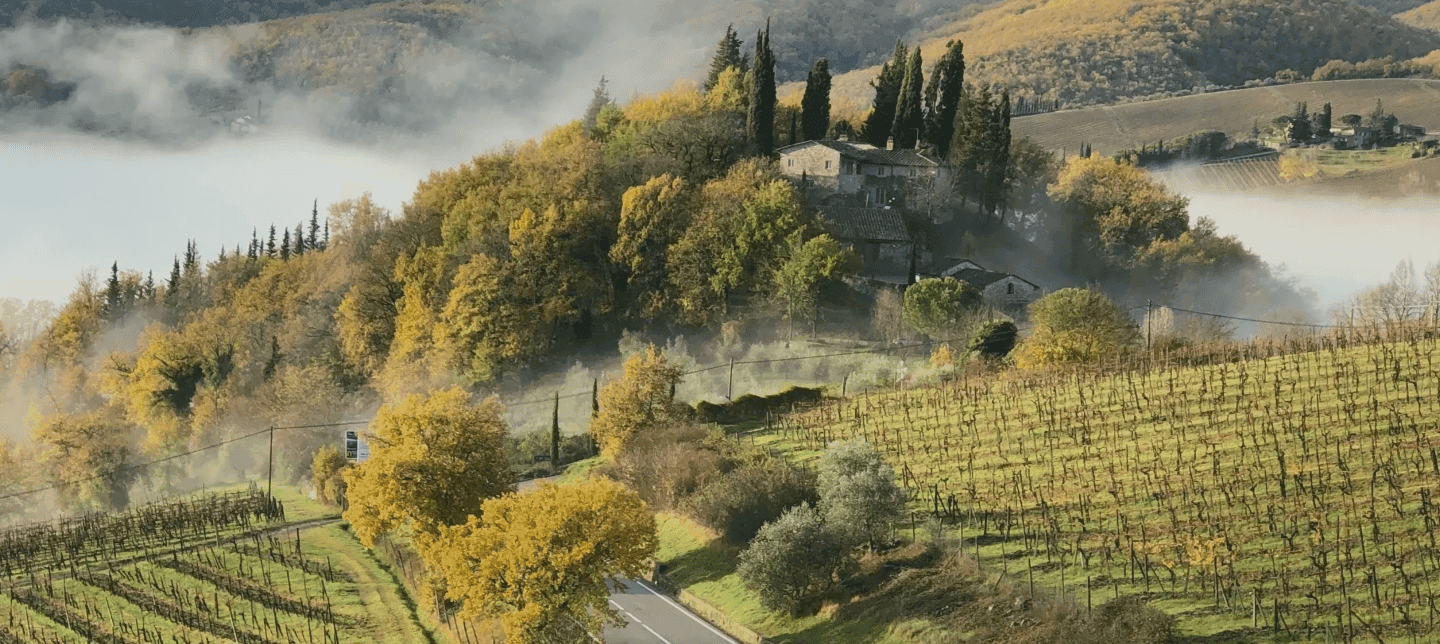

Why Chianti Classico Is Finally Changing (And What It All Means)

One of the most traditional regions out there is suddenly a model for how appellations can evolve.

Christy Canterbury MW · Jul 11, 2024

In agriculture—and especially in wine—it takes years to see evolution amongst the vines and the wines. When it comes to European wine, things tend to change even more slowly or not at all. Dust collects on bottles. The current generation nods in acknowledgment at the wisdom of their elders. Besides, change is inconvenient—especially when 480 producers in a 100-year-old consorzio, or trade association, are involved, like in Chianti Classico. In Europe, vinous heritage is to be preserved, not evolved.

Except in Chianti Classico. There, change is becoming a habit. Of course, it hasn't always been so.

In the 1970s, ‘80s, and even into the ‘90s, the image of Chianti Classico was wrapped up in the budget-friendly, generally mediocre-quality wine the region bottled in light bulb-shaped fiasco flasks covered in straw. The wines sold, but they did not promote an image of high quality.

Chianti Classico desperately needed to level up, and it has. This most Italian of all Italian wine regions has been giving itself makeovers left and right over the last two decades.

How so? The wines have soared in quality, and they now offer a clearer sense of place. Defining the wines and the production zones has been greatly aided by the release of Alessandro Masnaghetti's map (read on for more details). Moreover, the consorzio's introduction of a new classification, the Gran Selezione DOCG—starting with the 2014 vintage—now requires even more restrictive rules to achieve that designation. Gran Selezione is the region's highest quality wine. This third tier sits above the former top-quality wine, Chianti Classico Riserva, and the entry-level Chianti Classico. Another twist in the Gran Selezione category is that all grapes must be grown by the producer—no purchased fruit allowed. As of July 1, 2023, Gran Selezione labels can finally includes UGAs, too, on any wine not yet released from the winery, regardless of the vintage. A UGA (Unità Geografiche Aggiuntive, or Additional Geographical Unit) is a sub-zone, and the Masnaghetti maps demarcate 11. A mere six percent of the region's production attains the Gran Selezione designation. All this plus the region's iconic Gallo Nero, or Black Rooster, motif that was originally chosen in 1384 was graphically modernized in 2013. It is as if Chianti Classico is writing a self-help book that many other European regions would greatly benefit from reading closely. To top it all off, in late June, the region submitted a candidacy dossier of “The Landscape of the Chianti Classico Farm-Villa System” to UNESCO for consideration to be included in the World Heritage List.

Manfred Ing, winemaker of Querciabella, told me, "It's hard to believe it's been against the law to put the UGAs on the labels until now. We introduced the Gran Selezione indication 10 years ago. It's been like having a grand cru [Burgundy] without listing the cru. Querciabella's Gran Selezione was entirely from Greve [a cooler part of Chianti Classico] in 2017, 2018, and 2019, but you wouldn't know that just by reading the label. In 2020, I added in fruit from the cooler, high-altitude and east-facing Lamole. In 2021, I also added fruit from Radda, which has some of the highest vineyards in the entire region." [Side note: Older vintages of yet-to-be-released Gran Selezione wines may also include UGA designations.There is also the hope that UGA mentions may be included on labels for normale and Riserva wines down the road.]

"We are making history this year!" enthuses Emanuele Reolon, the estate director of Isole e Olena, while beaming through a spotty, cell phone Zoom chat. He sways in the back seat as his driver navigates tight corners around the Tuscan hillsides, transporting him between vineyard visits. "It is a new era for Chianti Classico. It is a birth year!”

Dialing into a highly specific location is the sort of detail that wine lovers embrace, and Chianti Classico is steeped in diversity. It is large—the region stretches across 72,000 hectares, reaching from Siena to Florence. Its vines face every possible exposure and range from 650 to 2,300 feet in elevation. Alessandro Zanette, winemaker at Poderi Melini, pointed out that soil types vary vastly, too. "Move one kilometer from any given place in the region, and you can have a 100-million-year change in soil age!" He added, "Microclimates count for a lot, too. Only 10 percent of the region is planted to vines. The rest is mostly forests.” (These provide cooling and shading.)

Along with the microclimate and elevation, soil types go a long way in defining the final wine. Wines from pietraforte soils—rocky sandstones with high calcareous content—are firmer and show more structural backbone. Wines hailing from alberese soils—calcareous limestone—are more reserved and sometimes show a slightly angular structure. Macigno soils—blue sandstone that has eroded into sand—offer easier-going wines with less demanding structures, while wines from alluvial soils show the softest tannins are the most approachable. The classic galestro soils—rocky clays—deliver bold fruit.

The slicing and dicing of Chianti Classico into UGAs were performed in cooperation with Alessandro Masnaghetti, a nuclear engineer turned wine lover then wine journalist and now wine cartographer. Since 1994, Masnaghetti has meticulously outlined many of Italy's most prestigious regions, giving them more specific identities and valorizing the wines they produce.

Still, the UGAs can be relatively large, occasionally making generalizations tricky. Painting with a broad brushstroke, the individual UGAs more or less deliver these characters:

- Greve: generous fruit and age-worthiness

- Lamole: high-toned aromas and elegance

- Radda: vivacity and perfume

- Gaiole: power and structure

- Castelnuovo Berardenga: generous fruit and palate breadth

- Vagliagli: ripe fruit and easy-going drinking

- Castellina: ample acidity and crisp tannins

- San Donato in Poggio: bright aromas and a salty edge

- Panzano: muscular fruit and good ripeness

- Montefioralle: approachable fruit and supple texture

- San Casciano: pliable tannins and succulent fruit

Back to the Gran Selezione classification, there is another, equally pivotal level of clarity arriving with the 2024 Gran Selezione. Reolon said, "With the new rules, at least 90% of wine must be Sangiovese, and the rest is exclusively local varieties [like Canaiolo, Ciliegiolo, Colorino]. No more French varieties."

The microscoping-in on Sangiovese offers a more precise "sense of place" that otherwise could have been masked with a dollop of Merlot, Cabernet Sauvignon, or even Syrah (which are still allowed in the normale and Riserva wines). It also keeps the wines more elegant. The French varieties beefed up the wine styles and could absorb a lot more new, French oak. These changes set up Gran Selezione to be a more distinguished category, rather than a super-Riserva of sorts. Early on, some of the Gran Selezione seemed to be trying to mimic Super Tuscans, almost all of which rely heavily or even exclusively on French varieties.

In fact, the Gran Selezione wines may be better off without Merlot—at the very least—in the face of climate change. Both Ing and Zanette mentioned that Merlot suffers from water stress, while Sangiovese deals with it more easily.

With the arrival of the Gran Selezione classification in 2014, wineries began taking closer looks at their normale and Riserva wines, too. Ing pointed out, “Every time we add a wine to the Riserva, we take away from the normale.”

With all of these onboarded improvements, will the Gran Selezione wines age well? Absolutely. After all, these are the pinnacle of quality in the region. Besides, Chianti Classico and Chianti Classico Riserva can age brilliantly well. A tasting event that marked the 100th anniversary of the consorzio, held in late April in New York, featured wines going back 75 years. The 1949 and 1960 Chianti Classico Riserva Brolio from Ricasoli were still alive and inviting. A 1969 Poderi Melini Chianti Classico Riserva La Selvanella (tasted twice, from two different bottles on two different days) showed joyous integration and sustained flavors on the finish. A 1977 Ruffino Chianti Classico Riserva Ducale was lush and moreish. The 1981 Fontodi Chianti Classico Riserva sprang out of the glass with dazzlingly aromatic dried strawberries. The number of scintillating wines only increased as the decades became more recent. The 1994 Querciabella was very tasty, but the 1998 was ethereal.

What defines greatness in classic wines is ageability. Chianti Classico inherently—in its terroirs and especially its indigenous grapes—has this in spades, and the region’s collective efforts are pushing the limits to find a new pinnacle.

Chianti Classico Producers to Seek Out

Badia a Coltibuono

Castell'in Villa

Castello di Ama

Castello di Fonterutoli

Castello di Monsanto

Castello di Volpaia

Fèlsina

Fontodi

Isole e Olena

Istine

Lamole di Lamole

Monte Bernardi

Querciabella

Ricasoli 1141

Rocca delle Macìe

Rocca di Montegrossi

Ruffino 1877

San Felice

extendedBiddingModal.title

extendedBiddingModal.subtitle

extendedBiddingModal.paragraph1

extendedBiddingModal.paragraph2